In part one of this series, I explained why I want to replace my Vodafone router with an open-source solution. Today, the focus shifts to the hardware required for that setup. The main emphasis is on the router device itself, which will run OpenWRT, but I’ll also share my thoughts on the switch and access point.

Which hardware actually works well with OpenWRT?

Let’s start with the router. My plan is to install OpenWRT. Why OpenWRT instead of something like pfSense? I’ll cover the software and installation process in the next part. For now, I’ve committed to OpenWRT as the platform.

The open-source router operating system officially supports multiple CPU architectures, including Intel and AMD CPUs (x86), ARM (such as Raspberry Pi), traditional router SoCs used by many manufacturers (MIPS), as well as PowerPC. Each option comes with its own advantages and drawbacks.

Mini PC, ZimaBoard, or Raspberry Pi – what’s the best choice?

| Criterion | Router SoC (OpenWRT router) | Raspberry Pi | Mini PC (x86) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical use case | Traditional router | DIY / multi-purpose system | High-end router / firewall | ||

| Power consumption | Very low (3–8 W) | Low (5–10 W) | Moderate (10–25 W) | ||

| CPU performance | Low–moderate | Moderate | High | ||

| RAM / storage | Limited | Moderate (SD / USB / NVMe*) | High (SSD / NVMe) | ||

| Ethernet ports | 4–5 integrated | 1 (USB adapter required) | 2–6 dedicated NICs | ||

| Integrated switch | Yes | No | No | ||

| Wi-Fi quality | Very good (router-optimized) | Moderate | Depends on external hardware | ||

| 24/7 stability | Very high | Moderate–high | Very high | ||

| Maintenance effort | Very low | Moderate | Low–moderate | ||

| Expandability | Very limited | High | Very high | ||

| VPN performance | Good (WireGuard) | Good | Very good | ||

| Gigabit / >1 Gbit | Model-dependent | Limited | No limitations | ||

| Noise level | Silent | Silent | Passive or fan-cooled | ||

| Cost | Low | Moderate | Moderate–high | ||

| Recommended for | 24/7 home router | Learning & experimentation | Advanced networks |

Why I chose the Zimaboard 1

An OpenWRT-compatible router offers the lowest power consumption, making it the best direct replacement for a typical ISP-provided router, while a mini PC delivers the highest performance. However, I also wanted to factor in the hardware I already own: a Zimaboard 1, Zimaboard 2, ZimaBlade, a BMax mini PC with an Intel N95 CPU, and a Raspberry Pi Zero. I ruled out the Raspberry Pi because USB Ethernet introduces additional latency and an unnecessary point of failure. The same applies to the mini PC—it only has a single Ethernet port. USB Ethernet could be added, but that’s not an ideal solution for a reliable router setup.

A fully supported OpenWRT router would likely be the simplest option, but since I already have the Zimaboards available, they stand out as the best compromise between a mini PC and a traditional router. Each board includes two dedicated Ethernet ports, which is ideal for separating WAN (incoming internet from the modem) and LAN (connection to the switch). They are also passively cooled and, despite using an x86 architecture like a standard PC, remain relatively power-efficient.

Even a laptop could work as a router, but it would take up too much space in my setup. I ultimately chose the Zimaboard 1 because its Gigabit Ethernet ports are sufficient for my needs, and I plan to use the more powerful Zimaboard 2 later as a higher-performance home server. As an alternative, I would recommend a power-efficient OpenWRT-compatible router, ideally without enabled Wi-Fi, since wireless functionality is better handled by a dedicated access point.

Do you need a managed switch, or is a basic 5-port switch enough?

For now, I’m skipping the purchase of a new switch because I still have a basic 5-port Netgear switch available. In general, simple unmanaged switches are perfectly adequate and very affordable, starting at around €10.

If you plan to expand your network later with features like VLANs, a managed switch makes sense, although it typically consumes slightly more power. Ideally, the switch should support PoE (Power over Ethernet), which allows the access point to receive both power and data through a single Ethernet cable, eliminating the need for a separate power adapter.

Access point instead of router Wi-Fi: Wi-Fi 6, 6E, or Wi-Fi 7?

The final missing piece is the access point (AP), which provides the Wi-Fi network. Choosing the right model involves balancing price, wireless standard (Wi-Fi 6, 6E, or Wi-Fi 7), and power consumption.

Technically, you could use a traditional router in access point mode, but these devices tend to consume more power. Dedicated access points are a better option, as they’re more efficient and specifically designed for providing reliable wireless coverage.

Wi-Fi 7 access points are already available for under €100, such as the Ubiquiti U7 Lite. While it doesn’t support the 6 GHz band, it can deliver up to 4.3 Gbps on 5 GHz. For the same price, the Ubiquiti U6+ is also available. It doesn’t support Wi-Fi 7, but offers a slightly broader feature set.

Zyxel NWA50AX Pro in use – why I didn’t choose Wi-Fi 7

Since 4 Gbps wireless speeds would be overkill for my 1 Gbps internet connection—and my router (ZimaBoard) only supports Gigabit Ethernet anyway—I opted for a more affordable alternative: the Zyxel NWA50AX Pro.

I purchased it as a returned unit for just €55, which is more than sufficient for my needs. It features a 2.5 GbE uplink, allowing it to receive up to 2.5 Gbps via Ethernet, supports wireless speeds of up to 3,000 Mbps, and can be powered via PoE.

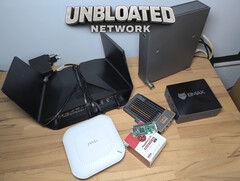

My hardware setup for switching to OpenWRT

Here’s the complete hardware setup for my OpenWRT project:

- Modem: The old Vodafone Station is repurposed as a basic modem that simply passes through the internet connection.

- Router: The ZimaBoard 1 becomes the router. It receives the internet connection from the modem, routes traffic between the internet and local network, and provides firewall and DHCP functionality. Alternative: any OpenWRT-compatible router.

- Switch: A basic unmanaged 5-port switch distributes Ethernet connectivity to wired devices.

- Access point: A Zyxel NWA50AX Pro with Wi-Fi 6 (AX3000) provides wireless connectivity.

What does switching to an OpenWRT router cost?

The ZimaBoard 1 is no longer sold, and the newer ZimaBoard 2 costs €279, which is relatively expensive. A more affordable alternative would be a budget OpenWRT-compatible router. All-in-one routers with OpenWRT exist, but my goal is to separate each network component.

If purchasing all hardware from scratch (using an affordable OpenWRT router instead of a ZimaBoard 2), total costs start at around €80 to €150. Naturally, costs can increase depending on the hardware chosen. Reusing existing equipment can significantly reduce the investment.

Typical hardware costs:

- Router: OpenWRT mini router starting at around €35

- Switch: starting at €10–€20

Access point

- 300 Mbps models starting at €30

- Wi-Fi 6 (1.8 Gbps) models starting at €35

Outlook: installing and configuring OpenWRT

In the next part, I’ll focus on the software side—specifically OpenWRT itself. I’ll explain why I chose it over pfSense and walk through the installation process on the ZimaBoard, which serves as a representative example for any x86-based router system.

Overview

- Unbloated network – Project overview (part 1) ✅

- Unbloated network – Which hardware actually makes sense? (part 2) ✅

- Unbloated network – Install and configure OpenWRT on the ZimaBoard or any other PC