Global campaign shifts from grassroots to legal battleground

What began as one man’s furious response to Ubisoft’s deletion of The Crew has grown into a multi-pronged international campaign to prevent the destruction of digital games. Ross Scott’s Stop Killing Games initiative—originally a video essay protest—mobilized millions and helped trigger legal inquiries, political proposals, and public pressure on both sides of the Atlantic. Among the key developments: consumer protection investigations across several countries, the European Citizens’ Initiative gathering widespread support, and growing interest from legal experts, regulators, and policymakers.

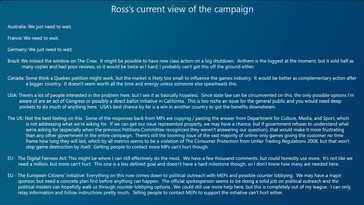

While much remains uncertain—such as the validity of over one million EU petition signatures or the final language of the Digital Fairness Act—Scott maintains that the movement has done everything within realistic reach. Most campaign avenues are now in a “wait and see” phase. Notably, Brazil’s legal angle stalled due to a lack of local sales data, but core markets like Germany, France, and Australia continue to press forward. Meanwhile, Scott has stepped back from front-line organizing, ceding future lobbying efforts to politically connected volunteers and allies.

Personal burnout meets hopeful legacy

In a deeply personal reflection, Scott reveals months of nonstop behind-the-scenes work, burnout, and frustration—not with supporters, but with a system that even allows purchased digital content to be deleted. “I never wanted this to be my calling,” he says, “but I knew I’d regret it if I didn’t try.” Despite fatigue and a desire to return to his original projects like Ross’s Game Dungeon or Civil Protection, he acknowledges that this may have been a unique moment of impact: “None of these legal or political actions would exist if we hadn’t pushed when we did.”

While Scott plans to support the remaining legal steps as needed, he’s clear that future efforts—like watchdog organizations or community-led oversight—must grow independently. He also expressed interest in projects that digitally reconstruct “dead” game worlds using static or semi-interactive AI tools, suggesting that even if games are lost, their immersive environments might still be preserved for posterity.

Delistings and censorship: more protections needed

Although Stop Killing Games has focused mainly on always-online games being rendered unplayable, recent events involving Steam and Itch.io removals have widened the conversation. Scott clarifies that while the campaign does not currently address storefront delistings or financial censorship (e.g., by Visa or PayPal), its core legal changes could help ensure that users can still back up and play their purchased games in the future—even if support is withdrawn.

However, he warns that nothing short of legislation will prevent delistings entirely, as platforms cannot be forced to continue selling a title. The ideal outcome, he says, is a system where publishers must give adequate warning and offline backup access before any game becomes unavailable. “Clear labeling doesn’t protect anything if the game no longer exists,” he states.

Conclusion: buying is not owning — and maybe piracy isn’t stealing after all

Ross Scott’s Stop Killing Games campaign has exposed a fundamental flaw in modern digital commerce: that buying a game often means nothing more than renting access at the publisher’s discretion. When a paid product can be deleted remotely without recourse, the moral argument against piracy becomes hollow — especially when preservationists and players are left with no legal alternative. The campaign hasn’t defeated game destruction yet, but it has cracked open the illusion of ownership, forcing lawmakers and the public to reckon with an uncomfortable truth: if you can’t keep what you paid for, then what exactly did you buy? And who’s really stealing from whom?