Windows on ARM: Where we are now and what the future holds

Introduction

With the arrival of Windows on ARM (WoA) devices in late 2017, Microsoft was the closest it has ever been to achieving its goal of having a traditional Windows desktop experience running on the low-energy ARM architecture.

The lead up to launch was full of fanfare about the magic of combining the utility of full x86 software with the efficiency of an ARM SoC. These new devices were going to be a godsend for the perpetual travelers, with their long battery life, always-on data connection, and instantaneous sleep and resume abilities. Business people, nomadic wanderers, and university students alike were going to be freed from seeking out awkwardly placed power outlets and spotty Wi-Fi connections. Microsoft and Qualcomm were confident, and Intel was worried.

The Initial Reception

The first pre-release review devices were sent out in December 2017, equipped with the at-the-time flagship Snapdragon 835 that had first appeared in retail devices almost a year earlier. This timing was unfortunate because it was the same month that Qualcomm announced the Snapdragon 845, immediately making the WoA devices seem like they were launching with outdated hardware.

The first reviews and benchmarks complained that performance in x86 applications was (at best) on par with Intel’s efficiency-focused Y-series CPUs, but most indicated that in key workloads they could be surpassed by the cheapest and most basic Celerons typically used in entry-level Windows Netbooks and Chromebooks. Here we had a couple of devices that retailed for $600-800 but performed like a device that cost one-third of the price. The small number of ARM-native applications performed significantly better due to the lack of an emulation layer (e.g. browsing in Edge ARM rather than Chrome or Firefox), but running software from both architectures was a big part of the sales pitch.

If the Windows Store was full of ARM-native versions of the major web browsers, streaming music services, office suites, password managers, VPNs, photo and video editors, and games, then the performance of emulated x86 software wouldn’t matter so much. But the concept behind WoA was to give access to the huge back catalog of Windows software, while also getting the sorts of battery life and connectivity benefits that come from mobile hardware.

Battery life and weight were two areas that WoA devices had already delivered on. The power efficiency was obvious, but the ability to fit all the necessary components into a smaller motherboard and heatsink footprint had a side effect that many overlooked. Notebooks with the same form-factor and footprint as existing x86 models were left with more space inside the shell to either be filled with a larger battery or left empty to reduce weight.

Unfortunately, what we were left with were devices that had great battery life and good portability but underperformed when trying to do the sorts of work that people expected from a Windows laptop.

For a more detailed rundown of the early situation, check out my colleagues article: Opinion | Windows 10 on ARM: DOA?

The Current Situation

The release of Snapdragon 850 devices has improved the situation somewhat. The Snapdragon 850 is a modified Snapdragon 845 designed for use in WoA devices. These higher binned chips are overclocked to 2.96 GHz, similar to how Asus uses higher binned Snapdragon 845 chips in its ROG Gaming Phone. The larger batteries used in WoA laptops offsets any (minor) change in power draw from the overclocked Snapdragon 850 versus the Snapdragon 845.

At launch, Qualcomm claimed that the Snapdragon 850 would offer a 30% performance improvement over the Snapdragon 835, just a small bump over the Snapdragon 845. Hitting that target was important to lifting the sub-Celeron performance up to a level that was good enough for light web-browsing, writing emails or assignments, and watching Netflix and YouTube. While that wouldn’t be attractive to power users, it would cover the original target market of the "average" student, traveler, or coffee-table PC user.

It was also at this time that more people started referring to WoA as "Windows on Snapdragon" (WoS). This distinction signified that these were now custom SoCs and helped to create a bit of marketing separation from the initial round of WoA devices.

The first commercial Snapdragon 850 offering was the Lenovo Yoga C630, which was announced in late August at IFA 2018. It was quite an appealing device with a 13.3-inch FHD screen, 1.2 kg weight, 2-in-1 form factor, pen support, always-connected LTE, and a claimed 25-hour battery life (video loop) thanks to the 61 Wh battery.

When we reviewed the Lenovo Yoga C630 ($850 MSRP), we found that software with ARM-native versions performed well. These included key software like Microsoft Edge and Microsoft Office, covering the vital combination of browser and office suite. This changed when we converted away from the more locked-down and controlled Windows 10 S to Windows 10 Pro. ARM-native software continued to perform well, but the traditional x86 applications we installed struggled just as they did on the original Snapdragon 835 devices. X86 benchmarks running in emulation now showed performance similar to the Intel Celeron N3350, an entry-level Apollo Lake CPU using the Atom architecture. But some reviews complained of frequent stutters and pauses, presumably due to the emulation.

We also couldn’t achieve the ultra-long battery life advertised by Lenovo using our battery testing software, managing to get less than half of the advertised life. In defense of WoA, we need to point out that this was a web-browsing simulation test rather than a video loop, and battery life might be better if the device is left in Windows 10 S mode. The battery life was still good at 11 h 51 m, but this puts it in the same league as the best Windows 10 x86 notebooks or some of the (much cheaper) Chromebooks.

The same can generally be said for Samsung’s Galaxy Book2 — a Surface Pro-esque 2-in-1. While we never reviewed the Galaxy Book2, the specifications and reviews from others around the web indicate that there shouldn’t be any difference here, apart from the MSRP being $150 higher.

WoA is currently at a stage where it is useable in some situations but still isn’t ready for wider adoption.

The Future Improvements

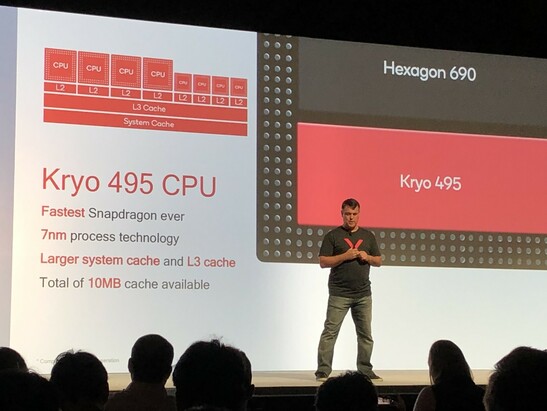

In recent times, Microsoft has built a reputation for killing off projects that aren’t performing well, but that doesn’t seem to be the case for WoA. Qualcomm is also showing dedication, with the Snapdragon 8cx — a 7 nm 7-Watt product designed to compete against x86 systems with 15-Watt TDPs — announced in December 2018 at the Snapdragon Tech Summit. The 8cx uses four modified Cortex-A76 cores (Kryo 495) and four power-saving Cortex-A55 cores and features the high-performance Adreno 680 GPU. The Snapdragon 8cx can be expected in Q3 2019.

This design is noticeably different from the Snapdragon 855, although this hasn’t stopped the comparisons. However, it’s actually more important to compare it to the previous generation Snapdragon 850, as the fastest current WoA chipset. There aren’t many performance details for the CPU cores but if the four "BIG/performance" cores are anything like the prime core in the 855, then it should be a favorable comparison. The GPU is claimed to be 60% more efficient while also being 100% (2x) more powerful, and another key improvement is the inclusion of NVMe drive support. This change to storage spec might not sound like much, but manufacturers now have the option to use proper PC-class drives that have higher IOPS rates that result in better random read/write performance.

This improvement in hardware is welcome, but many of the performance complaints that we (and others) had come about when trying to run x86 software. The situation was made worse by the lack of developer tools to produce native ARM software for the Windows platform. Fortunately, this is set to change thanks to the November 2018 Visual Studio 15.9 update, which added support for developing and recompiling ARM64 applications.

At the same time, Microsoft announced that the Windows Store would also now allow the listing and distribution of ARM applications. Developers can still choose to distribute via other methods, but distribution via the in-built store will ensure consumers are getting the correct version without having to decide between x86, x86-64, or ARM64.

The nightly alpha releases of Firefox ARM and the rumored adaption of the open-source Chromium browser (the software behind Google Chrome) are two examples of developers creating ARM versions of x86 software.

Summary

After a shaky launch and an extended release schedule that was a cause for concern among WoA enthusiasts who suspected that Microsoft might be about to kill off another fledgling project in the early stages, WoA looks like it is finally starting to shape up. The hardware has improved greatly, and the software situation is catching up as first- and third-party developers take to the platform.

WoA has a clear set of strengths, and the weaknesses are slowly being whittled down. Performance might not quite be there to a level that will satisfy most people, but it looks like we’re not far off the point where ARM becomes a viable alternative architecture for those who need a light-weight ultraportable device with marathon battery life and always-on LTE data.