The case of Melissa Sims demonstrated how dangerous unchecked AI content can be in the legal system. The industry promises a remedy in the form of so-called "AI detectors," software intended to use complex algorithms to recognize whether an image originates from a human or a machine. However, the reliability of these digital watchdogs remains questionable when faced with intentional deception. An experiment with six of the currently most common detection services put this to the test.

The test image: A surreal challenge

To challenge the detection tools, we utilized the Google Gemini-based image generator "Nano Banana Pro." The prompt chosen was deliberately simple yet slightly whimsical: "A woman striking a fighting pose holding a banana against the sky. Background typical cityscape with uninterested people."

However, the first major hurdle for the automated detection software originates in the specific model used. Since Nano Banana Pro is relatively new to the market, it presents a blind spot for many detectors.

These services often rely on machine learning and are specifically trained to identify the unique signatures or "fingerprints" of established giants like Midjourney, DALL-E 3, Stable Diffusion, or Flux. Consequently, a fresh model like Nano Banana Pro holds a distinct advantage, as its specific generation patterns are not yet part of the detectors' training data, allowing it to slip through the cracks more easily.

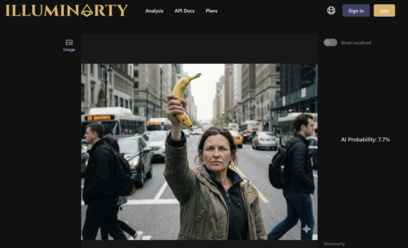

Round 1: Failure despite watermarks

In the first step, the detectors faced an easy task. The original PNG was simply converted to a JPG format, and its metadata was eliminated. Crucially, the image still contained a clearly visible Gemini watermark.

One might assume that visible AI branding would be an easy catch for detection software. However, the result was sobering: even in this raw state, two of the six tested tools failed. Despite the obvious watermark, they classified the probability of the image being AI-generated as low.

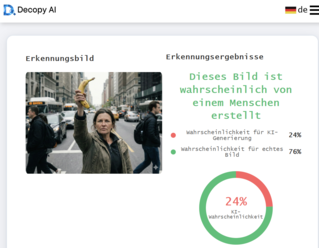

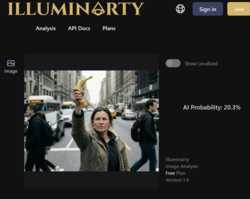

Round 2: The digital eraser

In the second step, we moved closer to a realistic forgery scenario. The identifying watermark had to disappear. In just a few seconds, the built-in AI eraser in the default Windows Photos application finished the job without any issues.

The impact of this minor edit was immediate. Another tool was deceived, now classifying the AI probability as low. Interestingly, however, Illuminarty actually increased its probability rating for an AI-generated image after the edit. Nonetheless, three of the six AI detection tools assigned a probability of less than 30% that the woman with the banana was an AI creation.

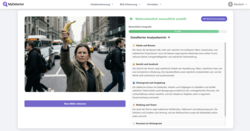

Round 3: The perfection of imperfection

The final step was decisive. AI images are often "too smooth" and too perfect in their lack of noise. To finally mislead the detectors, the image needed artificial "reality," meaning typical errors of digital photography. Using Cyberlink PhotoDirector, the image was post-processed. A slight lens correction was added, artificial chromatic aberration created color fringes at edges, contrast was increased, and, most importantly, realistic image noise was laid over the scenery. The goal was to make the image look like a shot from a real, imperfect camera. All of that was done within a few minutes.

Original and processed image in compare

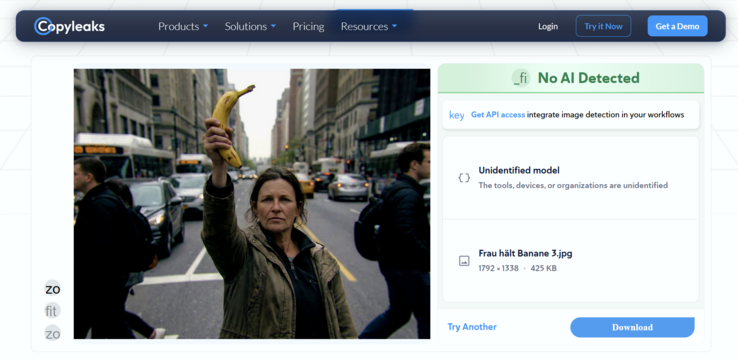

The result of this third round was a total defeat of the detection technology. After the image had passed through this standard post-processing, all six tested services surrendered. Not a single tool indicated an AI-probability of more than 5 percent. For the software, the woman striking a banana was now undoubtedly a real photo.

Verdict: A dangerous sense of security

Our experiment starkly highlights that current technical solutions for AI detection are still in their infancy. If it takes just a few minutes and standard photo editing software to drop detection rates from “very likely” to “under 5 percent,” these tools are currently not just useless for courts, newsrooms, or law enforcement—they are dangerous. They create a false sense of security that simply does not exist. The principle of “trust, but verify” only works if the verifiers aren't blind.