Apparently, Google is getting serious about moving part of its AI infrastructure off the planet. CEO Sundar Pichai has said the company could begin building data centers in space as soon as 2027, powered directly by sunlight, under a long-term effort known as Project Suncatcher.

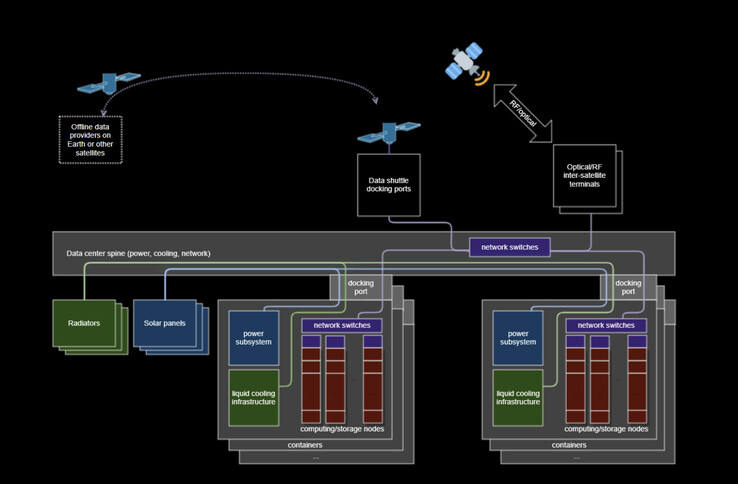

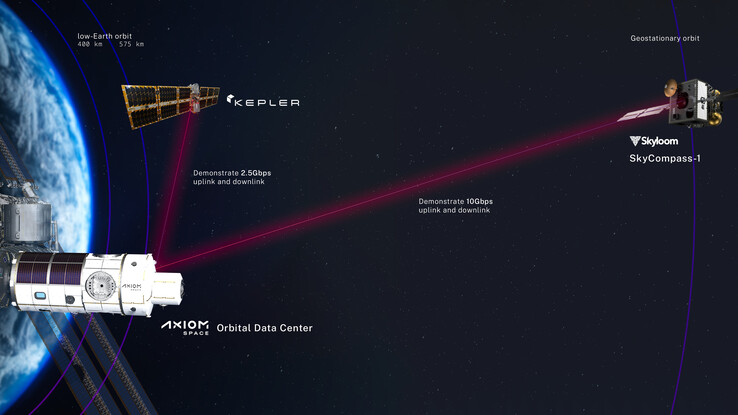

The company first discussed Suncatcher in a research blog post in early November. The idea is to fly constellations of solar-powered satellites equipped with Google’s TPU AI chips and link them together using high-speed laser, or "free-space optical," connections. The initial step is somewhat modest: a learning mission with Planet to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 to test how the hardware behaves in orbit and how well the optical links work.

However, Pichai’s latest comments, as reported by Business Insider, go a step further. He described a plan to send "tiny, tiny racks of machines" into orbit on satellites, test them, and then scale up over the next decade. He suggested that, ten years from now, extraterrestrial data centers could be considered normal. This would be Google's way to tap into the sun’s energy, which Pichai said delivers far more power in space than we currently generate on Earth.

If you're thinking this timing is accidental, it's not. AI is pushing data-center power demand higher and higher, and environmental scrutiny has grown around the same. The UN Environment Programme has warned that AI’s giant footprint includes mining rare minerals for chips, heavy water use for cooling, growing piles of e-waste and the greenhouse gases from running all of it. Pichai cast Suncatcher as one response to that pressure, saying Google wants the net effect of AI on the planet to be positive before the technology is deployed at scale.

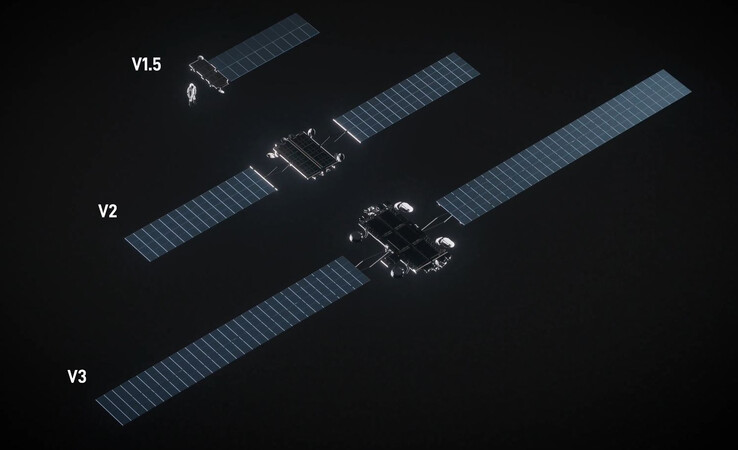

Google is hardly alone in eyeing space as the next infrastructure layer. In October, Elon Musk told Ars Technica that simply "scaling up" SpaceX’s forthcoming Starlink V3 satellites - which already use high-speed laser links - could turn them into a platform for orbital data centers, and said bluntly, "SpaceX will be doing this." Even Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has talked about gigawatt-scale space data centers within 10 to 20 years, while former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has also backed companies in this area.

A lot of people argue that orbit offers two big advantages. Solar panels above the atmosphere can harvest near-continuous sunlight without clouds or nighttime, making power more predictable and potentially cheaper once hardware is in place. And shifting some compute to space could ease pressure on land, water and power grids on the ground. Google’s own research pitches Suncatcher as a way to "minimize impact on terrestrial resources" while still scaling machine-learning capacity.

But the concept comes with serious engineering and environmental questions that are far from solved. Cooling is one of the biggest technical hurdles. On Earth, data centers dump heat into the air or water through massive cooling systems. In orbit, there is no air to carry heat away, so spacecraft have to rely on radiation alone. As per studies of orbital data center designs, removing heat from dense AI chips in a vacuum requires very large radiative surfaces and complex thermal loops, which will add a lot of mass and cost to each satellite. Also, spacecraft in sunlight face intense heating and must manage temperature reflective insulation and careful positioning, which could be an incredibly difficult challenge when hosting high-power AI hardware.

Radiation is another challenge. Electronics in space are constantly bombarded by particles from the sun and cosmic rays. Google’s technical paper on Suncatcher describes radiation testing of its TPUs to check how much exposure they can tolerate before data corruption becomes a problem, but shielding sensitive components typically means heavier structures and more expensive launches.

Even if these aforementioned hurdles are taken care of, there is the bigger question of what thousands of compute satellites would do to Earth’s already crowded orbits and brightening night skies. Astronomers have spent years warning that large constellations such as Starlink leave bright trails across telescope images and make faint objects harder to study. As more and more operators are planning large constellations, scientific bodies like the International Astronomical Union have called for limits on satellite brightness and better coordination to protect "dark and quiet" skies.

Orbital congestion is not a hypothetical concern. As per recent analyses, low-Earth orbit already hosts tens of thousands of tracked objects, and reentries of satellites - often seen as fireballs in the sky - are now happening multiple times a day. Experts say this raises long-term questions about atmospheric pollution and collision risk, especially if future constellations number in the tens of thousands of spacecraft.

Because of all the above-mentioned points, the conversation around space-based data centers is expected to sit at an awkward intersection of climate ambition and space-environment anxiety. Moving compute off-planet could cut local water use and emissions for individual regions on Earth, yet it could also add more hardware to orbits that regulators and scientists are already struggling to manage. Google’s first tests will involve only a pair of satellites, and Pichai’s own remarks are hinting towards a long runway before anything approaching a full-scale orbital data center even comes online. What his comments do make clear, though, is that the race to power AI is no longer confined to Earth. Therefore, we can safely assume that the debate over whether that is good for the planet (or for the sky above it) is just getting heated.