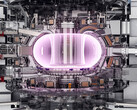

The road to a commercially viable nuclear fusion reactor is rocky. Well, only figuratively, because it is actually hot, far too hot. 150 million degrees (270 million °F) for a stable fusion of hydrogen isotopes to helium must first be managed. The effort involved is correspondingly gigantic.

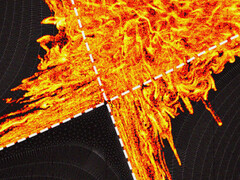

In addition, calculations and experiments suggest that turbulence in this plasma, which is ten times hotter than the interior of the sun, leaves its containment in a relatively concentrated area. Although this is less true for the various research reactors, models suggest the same behavior for a large amount of plasma that will be used in the nuclear fusion reactor ITER.

The result would be frequent shutdowns, as such hot matter would burn through anything that crossed its path as soon as it had overcome the magnetic fields enclosing it. This would make it all the more difficult to achieve the goal of obtaining more energy than flows into the reactor for heating and containment.

However, this idea could soon be outdated, in two respects: new simulations carried out with the software X-Point Included Gyrokinetic Code show a different behavior. One of the reasons for this is that additional factors are taken into account here. These include so-called homoclinic turbulence. Such plasma eruptions return to their starting point and do not leave the containment of the reactor.

Overall, the improved and correspondingly more complex investigation showed that the range for outbursts is around 30 percent larger. Above all, this means that the extreme heat is not concentrated in a very small area and is therefore more manageable.

Furthermore, these less critical turbulences of the plasma can be specifically prevented. The introduction of elements such as neon reduces the probability of eruptions because the turbulence can be slowed down exactly where it arises.

And what does that mean now? If the new forecasts and models are correct, ITER can be operated much more efficiently than previous calculations have suggested. The plasma would be a little easier to control and the probability of emergency shutdowns would decrease. Or other simulations with a similar, possibly higher significance could come to a different conclusion in the future. Further research must and will be carried out here.

There is still some time, as even according to optimistic estimates, ITER will not start operation for at least 10 years. Then the models can be put to the practical test.